July, 2013

India is fast moving on reforming its welfare system by providing a unique identification number to all its citizens— of which the biggest advantage is believed to be accrued to people who live below poverty line or who face challenges to claim any welfare benefits. The country is targeting to enroll about 600 million people under the scheme known as “Aaadhar” by 2014, almost double of what the current enrollment stands at. The entire initiative will pave the way for an electronic system to deliver welfare programs to its citizens by providing a unique identification number and track these welfare payments.

While there is little doubt that such an initiative could reduce corruption, wastages and inefficiencies in its public delivery system, the question is to what extent can India dramatically improve development outcomes based on its transformed system of delivering subsidies? Can India replicate the success of countries such as Brazil and China in scaling up its welfare system and being able to rapidly deliver benefits to a large number of population in a short time frame? China has already embarked on an ambitious program of providing health care to its rural citizens. Brazil started the process way back in 1988 when it amended the constitution in 1988.

How did these countries achieve this? What lessons can India’s “BRIC” comrades offer when it comes to scaling up its welfare system?

Institution transformation: Formal versus Informal

China:

Under the current health care system, local governments in China spend a significant share of their budget on healthcare and social expenditures while the central government contribution is much lower. Over the years, the local governments in China have emerged to be powerful actors, both on the expenditure as well as revenue front.

But how did local governments in China become so powerful?

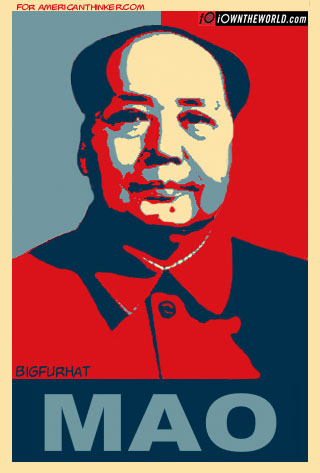

The historical context of this transformation dates back to the leadership of Mao, according to Jean Oi, scholar of Chinese politics at Stanford. Mao’s system of setting production targets for food and industrial production institutionalized a system where each level of government contracted “targets” on the revenue front with the subsequent level of government. This spawned indirectly a system of performance-based management where the government set performance targets and tracked indicators at the lowest level. Jean calls them village governments due to the their entrepreneurial spirit. The pressure to raise revenues and meet the performance standards from higher level of governments forced the local units to become more dynamic in their engagement with businesses.

Thus the process of institutional transformation in China was initially informal, where the system of setting performance targets and meeting them for industrial production triggered such a system for social sector program. Today, however, local government officials’ performance is assessed not just on economic growth and industrial development in their territory but also based on human and sustainable development. Each of this component gets an equal weight, and decisions regarding revenues transfer and bureaucratic promotions are tied to achieving these overall targets and performance benchmarks on economic and human development front according to a study on “Performance Management in People’s Republic of China: A study of accountability and vertical control in the implementation of public policy” by Burns & Zhiren in 2010.

Brazil:

Contrary to China, the process by which the role of local governments dramatically transformed in Brazil was more formal. The 1988 constitution amendment was a major turning point in the history that declared health as a right and mandated allocations towards health and education from the federal government as well as local governments. Local governments share of public spending increased from 18 to 22 percent, almost 3.5 percent of GDP, cites an article on “Brazil’s System of Local Government, Local Finance and Intergovernmental relations,” by Souza & Celin.Furthermore in 2002 there was a constitutional amendment which required local governments to earmark 15 percent of their budgets as well as from constitutional transfers to health programs (Souza).

Municipal elections were already taking place, but combined with their increasing clout in allocating budgets, policy innovations began to emerge at the local level. Several innovations in governance such as participatory budgets, cash transfer programs were experimented at the local level, which were then replicated across several cities.

India

When it comes to India a major point of institutional transformation has occurred with the National Rural Health Mission, which is changing the role of local governments or the “panchayati raj institutions” by giving them more planning powers. Though the 73rd amendment was supposed to change the role of local governments, the process has still been gradual. Since the Panchayat Empowerment and Accountability Incentive Scheme launched in 2005-06 and attempts to deepen the devolution process by launching the devolution index, local government’s capacity to raise revenues and spend is still very low compared to countries like Brazil and China. According to the Devolution Index in India latest report, there has been expansion of the local government’s responsibilities in planning and execution of projects and schemes sponsored by the central and state governments, taxes and spending powers still continue to be very low. As of 2012-13, share of local governments as a part of state government’s revenue is still barely 1 percent or even less for most of the local government institutions.

Institutional transformation at local level through UIDAI:

At present, UIDAI is developing a system to make electronic payments to welfare recipients and has the capability by which a government official at any level will know the status of the delivery or payment to a beneficiary. In the future this could very well pave the way for the government at each level to track far more indicators and outcomes. For instance, in case of beneficiaries under NRHM’s health insurance schemes for the poor, UIDAI could make it possible to track other indicators such as utilization level of the beneficiaries, hospital admission rates, readmission rates, duration of the hospital stay and other quality indicators for health outcomes. And based on these indicators for the welfare scheme recipients, local governments could infuse more power in terms of getting more resources from the higher level of governments or could use the same to battle their electoral turf wars. In Brazil, policy innovation has occurred at the grassroot level thanks to the electoral and fiscal clout of the local actors. In contrast China lacks electoral power but strong position of local governments to spend on welfare programs and raise revenues for the central government has made it possible to enforce accountability from the central government and rapidly scale up its welfare programs.

Mao may well have said that power flows from the barrel of the gun. Today the situation is power flows from the purse strings of the local governments.