When I took a class in International Development at Duke, one of the lessons I learnt from my Professor, who has been herself a county manager for World Bank for several years, was on donor coordination. While this was a theoretical lesson that I harbored for a few years, it was not until very recently that my own research brought me close to this reality. Lack of donor coordination has long been a buzzword when it comes to prioritizing development investments and strategies, but not much is said about the lack of coordination on the intervention front. Since I have been working on Bangladesh since the past one year, I think it is a fertile battle ground for donors investing in different projects, implementing different interventions, and producing evidence. But what is missing is connecting the dots between these different interventions:

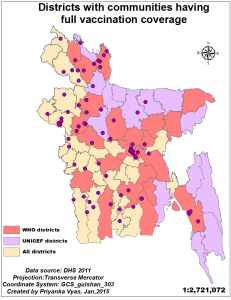

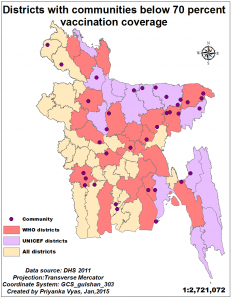

For example, in 2006 UNICEF identified about 14 low-performing districts to improve vaccination coverage. In 2007 WHO adopted another 23 districts that it regarded low on certain vaccine indicators. If you look at the above maps, you will see the districts adopted by WHO and those adopted by UNICEF. Each point on the map represents vaccination coverage for a community-level of 20-30 households has been high or very low based on the Demographic and Household Survey for Bangladesh, Historically, Sylhet and Chittgong have always had low health indicators because of hilltracts and low-lying areas. And this pattern is also evident on the map. Most of the pockets of communities with below 70 percent vaccination coverage fall in these intervention districts. The good news is that the interventions are targeted in the right geography and most communities with full vaccination coverage are outside these low-performing districts. But what can we say about communities with vaccination coverage between 80 to 90 percent and 90 to 95 percent coverage? There are several pockets of high immunization coverage in these low-performing districts and those which lie outside of these districts.

While WHO and UNICEF have been adopting districts for intervention, the Demographic and Health Surveys — which also provide GPS location data—- provide a classic opportunity to target interventions at the community level . Since district level aggregate data often mask variations in terms of pockets of low coverage and those with high coverage, location information at the community level can be a very useful tool. Unfortunately, despite all the efforts underway to collect spatial data, integrating it as a policy tool among different development agencies seems like a marriage yet to happen!